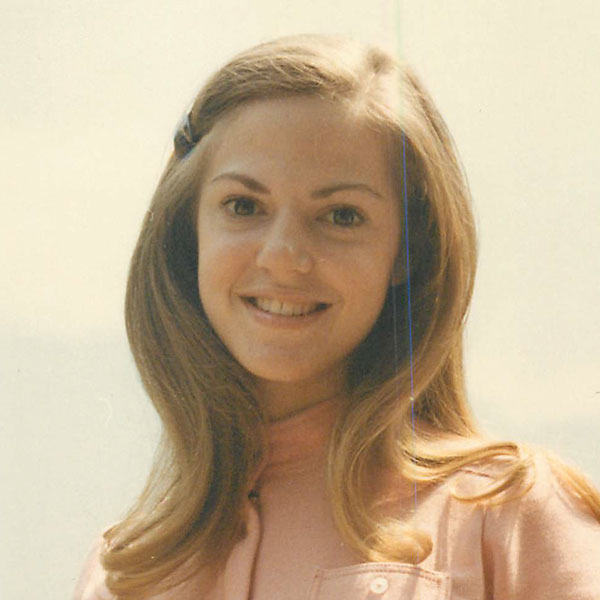

A Speech, by Ann Brown

A Speech, by Ann Brown

I remember very clearly how it began. I was sitting crosslegged on the rug in my bedroom in the house where I grew up in Mobile, Alabama. I was talking long distance to Bryan Delaney, a first-yearman at the University who was a friend from my hometown. It was the fall of 1969 and he was telling me that the University of Virginia was going to admit women to the College of Arts & Sciences for the following year.

"Maybe you should apply," he said.

Those were innocent words -- words I would remember a little less than a year later when I was enduring the Siege of the Observatory Hill Houses. As Orientation Week unfolded, the upperclassmen came in packs and -- with sixpacks -- to roam the conveniently constructed balconies of the 11New Dorms11 to peer in at the new breed of student which had arrived on the Grounds. As the 1970-71 Corks and Curls later said, "It [had] been hard for some of Virginia's gentlemen to accept the women. Many just weren't sure how to act. Two hundred leering potential rapists camped outside the women's dorms in early September did not make for good public relations."

I remember those September nights in Watson House as if they were yesterday. We were living in a fishbowl. The memories of my first year, indeed of all four of my college years, really are Proustian, you know. Maybe it's because I was young then or maybe it's because some of those experiences were so intensely new and different. But they are indelible and easily brought to mind by the sight of a familiar place, the smell of boxwood or a particular quality of sunlight. When Liz Argetsinger invited me to speak today I was flattered and pleased to be asked and I knew that this speech would almost write itself because I remember those early years of coeducation at Virginia better than I remember what I did last week.

And twenty (20) years has given me some perspective on those events -- some perspective on the University and on America in 1970 and how the arrival of women at Mr. Jefferson's institution fit into that picture.

I now know that we -- those first 450 women in the College of Arts & Sciences -- were women in transition and we had arrived at a place that was certainly in transition, too. I have wondered many times what the coeducation experience would have been like if it had happened in the more conservative S0's or 90's instead of at the crescendo of what will always be known in America as the Sixties. (For those of you who were not born until about that time, let me explain. In terms of the attitudes which made the Sixties, the Sixties, 1970, '71 and '72 were much more part of the Sixties than 1960, or '61 or '62). Women came to Virginia when the University was in the midst of a sea-change. We were not fully conscious of that atmosphere because the Sixties were just the times in which we came of age. We were unaware of the history of the women who had preceded us in more limited roles at Virginia -- the opening of the graduate schools to women in the 1920's, the excellent Nursing School. It is telling that 1970 is looked upon as the beginning of coeducation because in the minds of most of the University Community, it was the College that really counted. Social norms had been changing at Virginia for a long time. "In loco parentis 11 was almost dead here when we arrived and the University was not about to turn back the clock.

When my sister went to Auburn University exactly ten years before I started college there were pages and pages of 11rules to live by" -- no shorts or slacks or -- God forbid -- bluejeans in classes or the cafeteria or virtually anywhere else on weekdays. There were housemothers, middle aged or older women who lived in the dorms and fraternity houses like your mother in absentia. And curfews -- 10 P.M. on weekdays and midnight on Friday and Saturday. And absolutely no men allowed above the first floor of the women's dorms. If your father helped you carry your boxes upstairs, you had to run around screaming "Man on the hall."

By 1970, the rules about clothing had changed at Auburn and other southern colleges but the curfews -- for women students -- were largely the same. In loco parentis still hung on in a last, desperate attempt to protect the flower of Southern womanhood.

But at Virginia, the men had parietal hours. Women were welcome in the rooms and suites of the men's dormitories all weekend and all but a few evening hours on weekdays. While upon close examination you can still find the rooms where housemothers once lived in the McCormick Road Houses and on Rugby Road, they were long gone by the time we arrived. My mother still has trouble accepting the fact that she installed her second daughter in a coed dorm. She probably would not have tolerated it except that I was an Echols Scholar and I had to live there.

The sexual revolution had preceded us to Charlottesville. I well remember when I first realized that the Resident Advisor in my suit had pushed the twin beds in her room together for a male overnight visitor.

And yet we women were in some very important ways still very much in transition. Our social lives were primarily composed of formal dates arranged by the male half of the couple. We wouldn't have been caught dead going to Rugby Road with a group of girls. We waited to be asked. I knew an attractive premed student who lied about her good grades on science tests for fear her male peers wouldn't want to go out with her. She is now a successful doctor who married her college boyfriend.

And yet most of us would not have considered going to a women's college. We didn't think of ourselves as making history at Virginia. Instead we were just moving into our rightful place as an integral part of University life. To use a word which was not so much in vogue then, but which is a good descriptive -- we felt empowered by the progress women had made and by the times. I didn't feel that I was breaking down barriers because I believed that making my mark in college life at UVA was the most natural thing in the world.

My attitude was not -- "Wow, look at me, I'm making history." Rather, it was -- "What took you so long?" Like the other women of the Class of '74, I was raised to believe that no option was closed to me because of my gender. And yet, the Women of '74 were not an ordinary group -- not just a cross-section of college-bound students. Ernie Ern, then Dean of Admissions, had taken a close look at some other ventures into coeducation like Princeton's which had been less than entirely smooth and successful and he determined to select students who were not just the brightest women who applied. Although there was no question that we were more than able to do the academic work, what distinguished us was our collective high school record as "doers," as joiners, as leaders. There were yearbook editors, student council and class officers, debaters, actresses, athletes and musicians. There were an enormous number of former high school cheerleaders.

Mr. Ern knew how to pick 'em alright because beginning the day we arrived on the Grounds, we fanned out through the University community joining things and beginning our irrepressible rise to the top. Women were quickly assimilated into college life. It was inevitable that a group of women so talented, so energetic and so ambitious would accumulate an impressive list of firsts in a single student generation.

Also, the times were conducive to our success. The University's student body was more liberal than it had ever been before or than it has ever been since. I felt 11left-out" in conversations with upperclass men less because I was a women than because I had missed the Strike in May of 1970. It was the Strike that was the watershed event in the life of the University in the minds of the students of the early '70s and not the admission of women, the admission of significant numbers of black students, the growth of the University or any other of the other significant changes taking place around them.

The Corks and Curls for 1970 - 71 devoted twelve (12) pages of pictures and text to the Strike and just two (2) pages to coeducation with an essay of only 432 words.

These were times of ferment in the nation and at the University. The civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, the academic freedom and free speech movements had found Mr. Jefferson's University. Hair was long. Coats and ties were history. The stencil-painted clenched fist -- the symbol of the Strike was still visible on the sidewalks and buildings on the Grounds alongside the symbols of the honoraries. Change was not only tolerated it was welcomed. It would have been politically unacceptable in the minds of many male students to object to the presence of women in their classes or their clubs.

But there were exceptions. The always-conservative Jefferson Society went through elaborate constitutional contortions to exclude women from membership but the persistence of my classmate Barbara Golden coupled with her exceptional oratoracle skills and the "smarts" that helped her graduate in just three (3) years as the top student in History finally won them over. And there were many Other firsts:

Janet Palmer was the first woman Resident Staff Co-Chair and the first woman member of the 13 Society. She won the 1974 Algernon Sydney Sullivan Award.

Mary Bland Love was the Cavalier Daily Business Manager and the first woman on the CD's Managing Board. Roberta Hitt was the first women on the Corks & Curls Managing Board.

In our third year, many of us were senior residents and program assistants in the Resident Staff Program.

After rising for three years through the editorial ranks and running unsuccessfully for Editor-in-Chief of The Cavalier Daily, in the spring of 1973 I founded The Declaration with three (3) men in my class as an alternate voice in student journalism. And finally, the honors which had come to our male peers who achieved success in student life began to come to us also. In 1972-73, Cynthia Goodrich became the first woman to live on the Lawn.

In 1973-74 there were 14 of us on the Lawn -- once again over-achieving compared to our percentage of the 4th year class. We were tapped for ODK -- after making it known in our first year that we weren't particularly interested in having a chapter of Mortar Board -- the national women's-only honorary. We were tapped for T.I.L.K.A. and the Raven Society. (But we were not tapped for Eli Banana).

Barbara Savage and I were tapped as the first black and white women members of the I.M.P. Society. But the Z Society held out for another year, taking their first woman, Claire Brittain, from the Class of 1975.

The honor which meant the most to me personally was winning the Pete Gray Award in the spring of my third year because Pete Gray of the Class of 1968 had been an exceptional example of student leadership who was also so loved by his friends and contemporaries that they raised the money for a scholarship in his memory. He was the kind of University student I wanted to emulate. It was his contemporaries -- graduates of 1967 and 1968 that interviewed the candidates and selected the winner. These were the real Old U Men -- the ones who were, by definition, most likely to be hostile to the idea of women in their college. To be given the award by them was a clear signal that I had accomplished something of value in their eyes.

We wanted to be part of the mainstream of University life and part of the student power structure. We succeeded partly because of desire and partly because changes in student attitudes and demographics had brought about the death of the Old U System where student political parties and influential fraternities had controlled access to the top jobs in student activities until shortly before we arrived. UVA had become almost a pure democracy. In the next few years the rest of the 11firsts 11 for women would be achieved -- Chair of the Honor Committee, Editor-in-Chief of the Cavalier Daily. etc.

I never felt hostility from the faculty. In fact, they recognized that the arrival of large numbers of women would improve the quality of the young scholars they were teaching. Later there would be a backlash among some men students. While I was still in Charlottesville attending law school, I saw the great "Peach Pit Controversy" unfold when a male student from an all-male institution to our south wrote a letter to the C. D. describing Virginia women as peach pits. A journalistic melee ensued. But today it's obvious that most of the objections are limited to small pockets of half-hearted resistance. And the role of women as fullyparticipating members of University life is taken for granted. I am keenly aware that an entire generation has passed since I entered the University because my nephew Will Edgar, a member of the second-year class, was born in the spring of my first year. The women who arrived in September of 1970 were not particularly interested in a separate identity for women. I remember attending a meeting of women with Annette Gibbs, an Associate Dean of Student Affairs -- the University had scrupulously avoided the title "Dean of Women." She had been contacted by the national headquarters of several sororities and she wanted to know if we were interested in starting chapters here.

I well recall one of my classmates making the statement that she had come to Virginia precisely because it did not have sororities. We also would not have been interested, as a group, in those days in a Women's Center or a Women's Studies Program or any of the other institutional embodiments of feminist culture. Perhaps we should have been more interested. But for most of us, sexism was an obstacle we would encounter later. In my case, when I entered the University's Law School in the fall of 1974 and encountered some living, breathing members of my very own generation who believed the women in the class were taking up a place which could have been filled by a man -- a traditional American breadwinner. And then (somehow still naive enough to think that all the trails had been blazed and chauvinism was a dying vestige of a bygone era), I moved to New Orleans and began to pursue my chosen profession in a sociological backwater still largely untouched by the progress of the second half of the 20th Century ... But that's a topic for another speech.

Let's just say that each of us has found the Real World to be a less welcoming place than the University was. The challenges of our diverse careers, and of life as wives or single mothers or as single women in the Eighties have been numerous. But while I did not set out to make history by coming to Virginia, I do take a lot of pride in being a member of that first class and in the "firsts" that I achieved. And I draw strength from my experiences here and from the friendships I made with those very special women who were part of those first years. I have lost touch with many of those women over the years but I have always known they were making their mark in life around the country and around the world. I have wished for a long time that someone would organize a reunion of us and I am grateful for all the work the organizers of these events have done.

In some ways I find it hard to assess from my particular vantage point as a member of the first class what the impact of coeducation has been. But clearly there have been many effects. I think that had women not come to the University and taken an interest in it, the University Guides would still be a low-profile activity for nerdy history buffs instead of a prize fought for tooth and nail by eager undergraduates both male and female. And we certainly would not otherwise be contending for a National Championship in college basketball!

In academics, the national prominence of some of our foreign language programs, the enormous growth of the studio arts and art history majors and even the 5-year Masters Degree Program in Teaching may well be the result of the presence of large numbers of bright women with interests in those fields. The "gentleman's C" is no longer considered adequate classroom performance. Today the University strives for what it calls "the margin of excellence." The impact of coeducation on competition for admission to all the University's schools has made that excellence a reality.

The fears of students and administrators that women would destroy the best traditions of the University were unfounded. There was concern that the Honor System would not survive the strains that other relationships between men and women students would place upon the student-run system. Those Doubting Thomases underestimated not only our women but also our men. Virginia women have cherished the old traditions and participated in the creation of some new ones.

I believe that most of the changes wrought by coeducation are subtle shifts in outlook and attitude. Although the 1970-71 Corks and Curls analysis of coeducation was brief, I think it was pretty accurate. It said, Va. has a new face, new legs, a new body, but most importantly, a new mind -- a mind that challenges the old one, that rattles its complacency with a gentleman's approach to academics and extra-curriculars. It is a mind with different perceptions and new intuitions. It is the mind of a person, an individual. It is not seeking group identity, but identity with the whole.